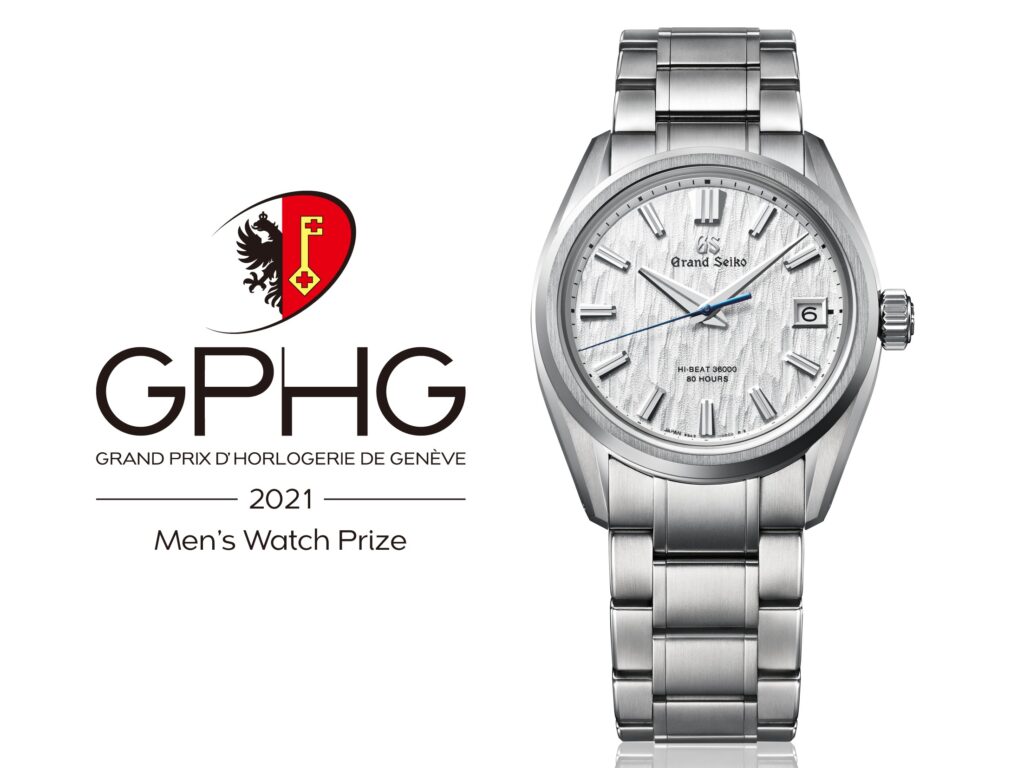

Grand Seiko, a wristwatch brand that Japan takes pride in, has been honored at the Geneva Watch Grand Prix, often referred to as the Academy Awards of the watch industry, by winning the Men’s Watch Award in 2021 and the Chronometry Prize in 2022. The wristwatches produced by Grand Seiko can be regarded as a culmination of the essence of Japanese craftsmanship.

On the other hand, Seiko offers wristwatches that express Japanese craftsmanship and aesthetic sensibilities through ‘Japanese traditional crafts.’ This is exemplified in the Seiko Presage Craftsmanship Series. In this article, I would like to introduce the charm of the Craftsmanship Series, which I deeply admire.

- The author’s journey of becoming obsessed with Japanese luxury watches and starting a blog

- The ‘Presage Craftsmanship Series’ shines a light on Japan’s traditional crafts and conveys the beauty of Japan through mechanical wristwatches.

- Inheriting and evolving Japanese traditional craftsmanship through watchmaking

- The reliable technology of Seiko

- The value proposition of ‘Quiet Luxury’

- The Value of Visiting Seiko Boutiques in Japan

- To embody a different set of values than those of European timepieces

The author’s journey of becoming obsessed with Japanese luxury watches and starting a blog

・Originally, I had no interest in luxury watches and used a Germin Android watch.

・I learned about the allure of luxury watches when I went to a jewelry shop accompanied by my wife.

・On the way home, I read a watch magazine and was drawn to the Seiko Presage Craftsmanship Arita porcelain model.

・I checked the actual Arita porcelain model at the Seiko shop in the nearby department store. I felt even more attracted to it than in the photos, and although I considered purchasing it, I went home without buying it that day.

・I thoroughly research information about luxury watches on the internet, focusing on Seiko products.

・I feel even more fascinated by the depth of the history of luxury watches and the various brands that weave it together.

・As I researched the history of Seiko, the feeling of wanting to support Japanese watch manufacturers arose (of course, I am also attracted to their products).

・I became interested in Grand Seiko and started researching about it on the internet.

・I watch a lot of YouTube videos about the Grand Seiko boutique and Shizukuishi Studio.

・A watch enthusiast acquaintance told me, ‘You should see a Grand Seiko in person at least once.’

・Furthermore, I’ve been researching Grand Seiko online and I’m quite intrigued.

・I went to the nearby Grand Seiko salon and was shown Shirakaba model (as well as the Yoru Shirakaba model).

・While feeling very attracted (especially to the Yoru Shirakaba model), I left the Grand Seiko salon unable to match the excitement I felt when I saw the actual Arita ware model for the first time.

・Heading to the Seiko shop in the department store where I saw the actual Arita porcelain model.

・I am shocked that the Arita porcelain model that was on display in the store has sold out.

・I checked the stock at the chain stores, but they all said they were out of stock. I came to realize that meeting a watch is a once-in-a-lifetime encounter.

・Search for Seiko Salon on Google Maps and go to the largest store nearby.

・I encountered the Arita porcelain model of craftsmanship again and purchased it on the same day.

・I wanted many people (especially those overseas) to know the charm of Japanese-made wristwatches, so I started a blog in Japanese, English, and Chinese.

The ‘Presage Craftsmanship Series’ shines a light on Japan’s traditional crafts and conveys the beauty of Japan through mechanical wristwatches.

The hallmark of the Craftsmanship Series lies in its dial. This piece pays homage to the ancestors who have led Japanese manufacturing and is a special model crafted using the techniques of traditional industries that have developed in harmony with the local community, namely ‘enamel’, ‘urushi’, ‘Arita porcelain’, and ‘Shippo enamel’.

Launched as a limited model in 2013, this series is anchored in the Japanese spirit of ‘monozukuri’ and has transcended traditional Japanese craftsmanship, such as enamel, lacquer, Arita-yaki, and cloisonné, into the watch dial. Its significance varies between domestic and overseas markets. For the Japanese, it reinvigorates pride in their rich artistic heritage and craftsmanship, offering the value of a lifelong item that harmonizes practicality and beauty. Meanwhile, for international consumers, it establishes itself as a distinct alternative to European watch brands, possessing unique Japanese artistry and narrative. This dual appeal indicates that this series is recognized not merely as a tool for measuring time, but as a cultural artifact.

The history of the Craftsmanship Series dates back to 2013 when Seiko released a limited edition model featuring an enamel dial to commemorate the 100th anniversary of its wristwatches. Seiko launched Japan’s first wristwatch, the Laurel, in 1913, and enamel was also used in the dial of the original Laurel. This model successfully integrated the timeless beauty of enamel, which does not fade with the passage of time, into mechanical watches, garnering high praise from the market. This success prompted Seiko to make a strategic shift, deciding to position Japanese traditional crafts at the core of its Presage line.

The History of Enamel

Enamel is a composite material created by fusing a glass-like glaze at high temperatures onto a metal substrate such as iron or aluminum. This technology enables the combination of the strong durability and high thermal conductivity of metals with the excellent properties of glass, such as luster, corrosion resistance, and non-adhesiveness. On the other hand, due to its glassy nature, it is susceptible to impacts and falls, and at edges where the glaze may not be fully applied, there is a risk of rust caused by moisture or salt. Nevertheless, the advantages of enamel outweigh its disadvantages, allowing it to play various roles throughout human history.

The history of enamel is extremely ancient, and its origins are believed to date back to around 1300 BC in ancient Egypt. The oldest example of this is the golden mask of King Tutankhamun. The enamel from this era was not based on iron, which is the prevailing material today, but rather on precious metals such as gold and silver, giving it a very high value as an ornamental item. This technique later spread to various parts of the world via the Silk Road, and within this flow, the technology was introduced to Japan from ancient times.

Throughout its long history, the value of enamel fundamentally transformed when it was later applied during the Meiji era for the extremely practical purpose of rust prevention for iron. The fact that enamel, which was an imported art and decorative technique, became intertwined with Japan’s spirit of practical craftsmanship resulted in a completely different path being taken. This represents not merely the introduction of a technology, but an important case where Japan’s social structure (the progression of industrialization) and cultural characteristics (pragmatism) redefined the role of foreign technology. This perspective will serve as the key to interpreting the subsequent history of ‘general products’.

The history of enamel as a practical commodity in Japan truly began during the Meiji era. Particularly noteworthy is the pioneering effort made in 1866 by Hirose Yosaemon, a large pot maker from Kuwana, during the era of Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last shogun of the Edo period. He applied a glass-like glaze, typically used for pottery, to the inside of iron pots as a rust preventative. This innovative idea transformed enamel from a decorative technique into an essential industrial material for everyday life. This technological shift suggests that Japanese manufacturing tends to optimize itself not merely by imitating foreign technologies but by adapting them to domestic lifestyles and challenges.

From the mid-Meiji period to the mid-Shōwa period, enamel signs established themselves as a dominant method of product promotion, marking a significant era. Numerous national brands such as Oronamin C, Bon Curry, and Kincho adopted enamel signs for advertising, which adorned street corners with their vibrant colors and durability. These signs were not merely advertisements; they served as a visual symbol of post-war Japan’s economic growth and the culture of mass consumption. Their durability provided a physical foundation for companies to maintain their brand images over time, seamlessly integrating into the urban landscape and becoming a symbol of nostalgia for the generations familiar with that era.

Peaking in the 1970s, the enamel industry entered a period of decline. The emergence of new materials, such as inexpensive and lightweight plastics and rust-resistant stainless steel, caused it to lose competitiveness in the market, leading many manufacturers to go out of business. Additionally, enamel signs gradually disappeared as their role was replaced by the acceleration of product cycles and the proliferation of new media such as television and newspapers.

Once relegated to obscurity with the advent of new materials, enamel has experienced a resurgence in value and appreciation since the 2000s. This shift reflects the contemporary societal trend where consumer values have transitioned from material wealth to a focus on spiritual richness and environmental consciousness.

Symbol of Nostalgia: Enamel signs have become highly valued among collectors as symbols of the Showa retro boom. This phenomenon is not merely an admiration for the past but is intertwined with memories of the vibrancy of the economic growth period and the warmth of a handmade lifestyle.

Reevaluation of Functionality: The inherent characteristics of enamel, such as durability, non-adhesiveness, and hygienicity, have once again drawn the attention of consumers. The aspects of being resistant to dirt and odor, and ease of maintenance, align well with the busy modern lifestyle.

Recognition as a sustainable material: Enamel, which is resistant to scratches and stains and can be used for a long time, is supported by environmentally conscious individuals as a ‘sustainable item’ in opposition to disposable culture. This indicates that it is not merely a relic of the past, but has gained new significance as a forward-looking material.

The history of enamel embodies the very spirit of Japan’s ‘monozukuri’—the craftsmanship that flexibly adapts foreign technologies to the Japanese environment and needs, merging decorative and functional values. Over the years, enamel has transformed its identity, evolving from ‘luxury goods’ to ‘mass-produced items’ and ‘sustainable materials,’ while consistently accompanying our lives and being rediscovered for its value. The continuum of enamel’s history, from the past to the present and into the future, eloquently narrates the cycle of ‘inheritance and innovation of technology’ inherent in Japanese craftsmanship, as well as the ‘resilience to thrive in times of change’.

The History of Urushi

The historical background of the term “Japan” serving as both the name of the country and a reference to “lacquerware” is rooted in the deep history of Japanese lacquer culture and its international recognition. When lacquerware was introduced to Europe, its unique luster and exquisite craftsmanship were praised, leading to its widespread acknowledgment as a symbol of Japan. This historical context not only indicates that lacquerware was an important export of Japan, but also narrates how Japan’s cultural identity has been shaped by this distinctive craft in the global arena.

The people of the Jomon period not only used urushi (lacquer) as a paint but also possessed highly advanced knowledge and skills in its processing techniques. A red wooden plate dated to approximately 5500 years ago has been discovered at the Sannai-Maruyama site in Aomori Prefecture, indicating that around 7000 years ago, the combination of red and black colors, as well as inlay techniques, had already been employed.

With the introduction of Buddhism during the Asuka period, the history of lacquerware entered a new phase. During this time, lacquer became an essential material for the creation of Buddhist statues and implements, establishing its technical value and religious authority. The Asura statue at Kōfuku-ji and the Nara period statues of the Eightfold Path at Tōdai-ji serve as representative examples of ‘datsukatsu-kanshitsu,’ a technique that involves layering hemp fabric with lacquer to create the images.

After the abolition of the Envoys to Tang China, the unique culture of Japan flourished during the Heian period, and lacquerware also underwent its own evolution, reflecting this aesthetic sensibility. It was during this era that the technique known as ‘maki-e’ was established, which involves painting patterns with lacquer and then sprinkling and adhering gold and silver powder. Maki-e became the ideal means to express Japan’s delicate and graceful sensibility.

The aristocracy formed a lifestyle that pursued beauty by adorning their furnishings, such as inkstone boxes and hand boxes, with maki-e and mother-of-pearl inlay. The National Museum of Tokyo possesses the national treasure ‘Katawakarikama-lakuta Hand Box,’ which is a typical example of this era that employs both maki-e and mother-of-pearl. Furthermore, at Chuson-ji Golden Hall in Iwate Prefecture and Hōō-dō at Byodoin in Kyoto, lacquer and maki-e were used within the interiors of these buildings, creating a majestic space that expresses Buddhist worldviews, particularly the Pure Land.

During the mid-Muromachi period, the popularity of the tea ceremony further deepened the role of lacquerware. At that time, expensive Chinese tea utensils were highly valued, and when they were damaged, the technique of repairing them with lacquer, known as “kintsugi,” emerged. This technique symbolizes an important cultural transition where the adhesive technology of lacquer that has continued since the Jomon period was elevated to “art” due to the aesthetic and spiritual demands of the Muromachi period.

Kintsugi embodies a philosophy that not only restores the functionality of an object but also decorates its cracks and chips with gold powder, emphasizing these imperfections as a new form of beauty instead of hiding them. This concept aligns with the Japanese aesthetic of ‘wabi-sabi,’ which positively embraces incompleteness and absence. It expresses a beauty that ‘does not conceal broken history but rather intentionally displays it, encapsulating time and memory.’ During this era, lacquerware evolved from being merely symbols of material objects or authority to becoming a ‘medium of culture’ that expresses specific ideologies and aesthetics.

Lacquerware embodies the beauty of utility, representing a high-level integration of both art and functionality rather than being merely an art piece or tool. The physical properties of lacquer, including its durability, water resistance, and antibacterial characteristics, underpin its long-standing use as a common household item. Rather than simply drying, lacquer undergoes a chemical reaction involving humidity and enzymes that allows it to harden, forming a robust film with excellent long-term performance. This durable coating grants practicality to lacquerware. Simultaneously, the unique luster of lacquer and intricate decorations such as Maki-e and Raden infuse beauty into daily life. Lacquerware profoundly reflects the Japanese value of harmonizing functionality and aesthetics, increasing in affection with each use.

The concept of ‘Wabi-Sabi,’ which underpins Japanese aesthetic sense, values simplicity, tranquility, and the beauty that arises from the passage of time. This spirit is most strongly embodied in the repair technique of lacquerware known as ‘Kintsugi.’ Kintsugi is believed to have originated during the Muromachi period for the restoration of expensive utensils in the tea ceremony culture; however, it is not merely a repair process. Rather than hiding the cracks and missing pieces with gold dust, it emphasizes these imperfections as a new form of beauty.

Kintsugi does not hide the imperfections of objects but actively embraces them. This philosophy is distinct from the general value system that favors perfection and novelty, as illustrated by the saying, “The beauty of cherry blossoms lies not in their full bloom, but in their falling.” It affirms both the history of an object that has been “broken” and the human will to “repair and continue using” it. The unique patterns created through kintsugi are one-of-a-kind, giving the object a new narrative and value. This spirit resonates with the modern concept of sustainability and symbolizes the deep-rooted Japanese culture of cherishing objects and their histories.

Lacquerware has dynamically transformed its social role from the Jomon period to the present, consistently existing at the center of Japanese life and aesthetic consciousness. It transcends the binary framework of mere ‘luxury goods’ and ‘common products,’ embodying a uniquely Japanese philosophy that harmonizes ‘utility’ and ‘beauty,’ ‘nature’ and ‘humanity,’ ‘time’ and ‘memory.’ In particular, the spirit of kintsugi reminds us of the universal values of cherishing objects and appreciating their histories, which is especially relevant in today’s society of mass production and consumption. Lacquerware is not merely a relic of the past, but rather wisdom and techniques that should be passed down as an integral part of Japan’s spiritual identity into the future.

The History of Arita Porcelain

Arita ware is a general term for porcelain produced in the region centered around Arita Town in Saga Prefecture, and is known as the oldest porcelain in Japan. Its origins can be traced back to the early Edo period, approximately four hundred years ago. The history of Arita ware is said to have begun in 1616, when the Korean potter Lee Sam-pyeong, who was brought back by Toyotomi Hideyoshi during the Korean invasions, discovered the clay used for porcelain at Izumiyama in Arita Town. This marked the first successful firing of porcelain in Japan.

At that time, the global porcelain market was dominated by Jingdezhen porcelain from China, which was also actively imported into Japan. However, with the intensification of the internal conflict accompanying the transition from the Ming to the Qing dynasty in China, the production and export of Jingdezhen porcelain temporarily plummeted. This event became a decisive external factor in the history of Arita porcelain, not merely a stroke of luck, but instead significantly contributing to the maturation of production systems and technology.

The cessation of supply of this Chinese porcelain triggered a chain reaction, resulting in a concentration of demand in Arita. The domestic and international demand for alternatives quickly focused on Arita. In response to this rising demand, Arita’s陶工 actively adopted Chinese techniques, achieving remarkable technological innovations. Particularly significant was the introduction of the technique of colored painting (akae), in which pigments in red, yellow, green, and other colors were applied over the glaze of the porcelain after the initial firing, followed by a second firing. This marked an essential step in establishing a distinct style, moving beyond mere imitation.

The porcelain fired in Arita was shipped from the nearest Imari port, and thus referred to as ‘Imari ware’ in domestic regions such as Edo and Keihan, while gaining recognition overseas as ‘IMARI.’ This ‘IMARI’ captivated European nobility from the mid-17th century to the early 18th century, swiftly establishing itself as a global brand. During that period, Europe lacked the technology to manufacture porcelain, making the ‘IMARI’ transported from the East not only exquisitely beautiful like a gem but also a luxury item that adorned the ‘porcelain rooms’ of palaces, symbolizing wealth and power.

The acclaim of Imari ware in Europe was a groundbreaking event that transcended mere Oriental taste, as it acknowledged the unique aesthetic sensibility of Japan on an international stage. This recognition stemmed not only from its luxurious decoration but also from Japan’s distinct sense of beauty. While typical white porcelain tends to have a slight bluish hue, the unique technique known as ‘Nigoshite,’ originating from the Saga dialect word for the water used to wash rice, produces a warm, soft milky white reminiscent of that rinsing water. This original base was born from Japan’s unique sensitivity that emphasizes the beauty of the material rather than opulence. Furthermore, in contrast to the densely painted ancient Imari, the Kakiemon style is characterized by a composition that makes the most of negative space, embodying Japan’s aesthetic sensibility of ‘the beauty of blank space,’ which is heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism and is believed to have significantly impacted European art.

Arita ware has played a multifaceted role as vessels that adorn both “Hare” and “Ke”. From premium offerings to shoguns and art pieces for European nobility (Hare), to everyday dishes that enrich the lives of common people (Ke), Arita ware has adapted its value and role throughout the ages, deeply rooted in the lives of all classes in Japan. The durable and aesthetically pleasing porcelain has brought enrichment and prosperity to the lives of the common people, becoming an indispensable part of the development of Japanese food culture.

Furthermore, the cultural value of Arita porcelain transcends mere historical heritage, playing a role in shaping the lifestyles and aesthetic sensibilities of modern individuals. When one holds an Arita porcelain vessel, the weight, texture, and the physical awareness that it may shatter if dropped contribute to fostering a consciousness that treats the act of ‘eating’ with care. This embodies a cultural and educational aspect that goes beyond the mere functionality of tableware. Additionally, the painting that depicts natural plants as they are and the composition that utilizes negative space suggest that Arita porcelain serves not only as a product but also as a medium through which Japan’s appreciation for nature and unique aesthetic values are transmitted to future generations.

Arita ware does not possess a singular history or value. Its history is a complex narrative interwoven with multiple contexts such as technological innovation, international trade, political intentions, and daily life. Moreover, each piece of this porcelain is imbued with the enduring spirit of people who, while being buffeted by the tides of the times, continue to uphold tradition and pursue innovation, reflecting the aesthetic sensibilities of Japan.

The History of Shippo Enamel

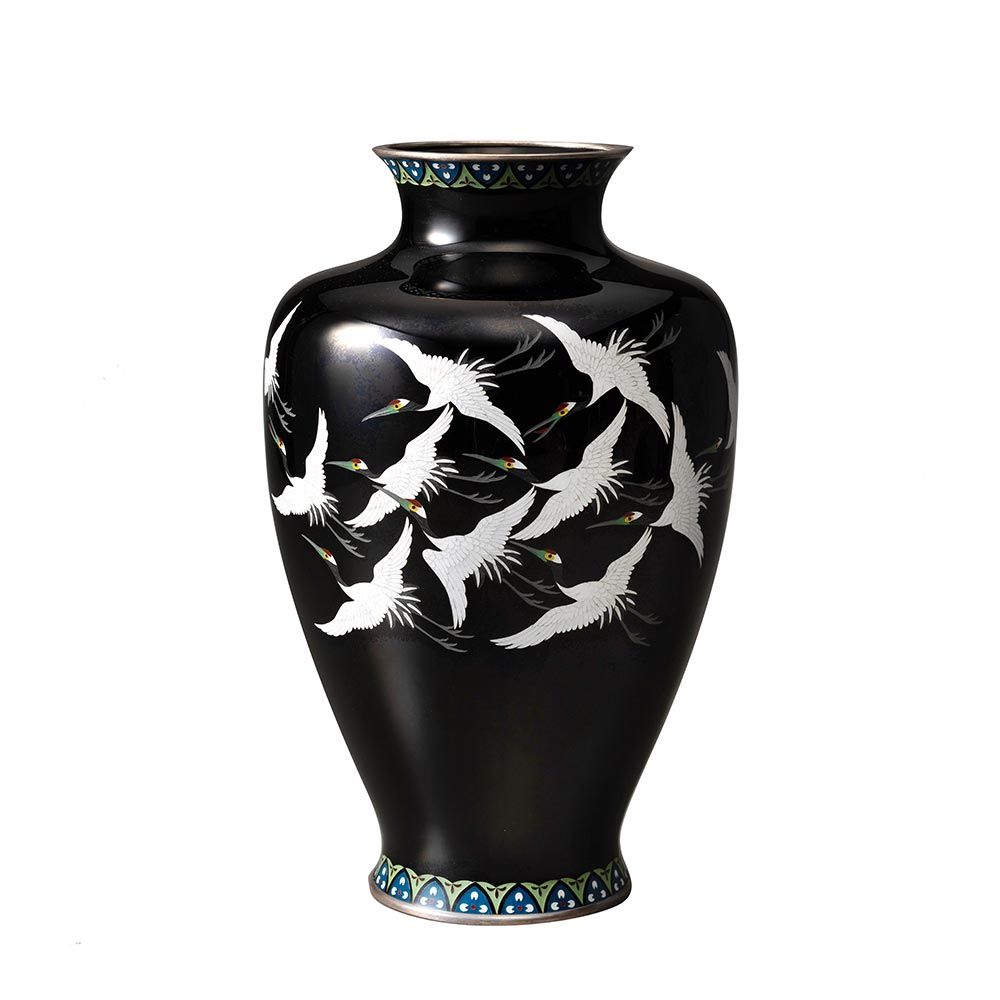

Shippo enamel is a traditional craft technique that expresses beautiful colors and patterns by firing glass-like glazes onto a metal base. The name ‘Shippō’ is derived from its beauty, as it is said to be comparable to the seven precious treasures mentioned in the Buddhist scripture ‘Muryōju-kyo’: gold, silver, lapis lazuli, glass, agate, coral, and jade. This etymology suggests that Shippō has long been recognized as an item of great value.

The introduction of cloisonné technique to Japan is believed to have occurred during the Asuka to Nara periods (6th to 7th centuries). This technique, brought by immigrants via China and the Korean Peninsula, was initially utilized as a decorative method in Buddhist art. However, subsequently, the cloisonné technique did not undergo widespread transmission within the country and entered a period of stagnation. This discontinuity in the technique suggests that ancient cloisonné was an exceptionally advanced and highly secretive craft, lacking a foundation for general dissemination, as well as being extremely difficult to produce. After developing as ornaments and furnishings for the nobility, cloisonné would enter an extended ‘blank period’ in the history of Japanese crafts.

The true resurgence of cloisonné in the spotlight of Japanese craft history occurred during the late Edo period, specifically in the Tenpo era (1830-1844). Kajiyoshi Tsunekichi, born in Habuto Village of Owari Province (now Nakagawa Ward, Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture), became captivated by cloisonné through literature and engaged in self-directed study of its techniques. A pivotal moment came when he obtained a Dutch cloisonné dish from an antique shop in Nagoya. By breaking that dish and studying its structure, he established his own unique method and successfully created a cloisonné bowl approximately five sun in size.

Due to this achievement, Kajitokichi is referred to as the ‘Father of Modern Cloisonné’. His revival was not merely a rediscovery of techniques, but rather was reflected in his subsequent actions. He distinguished himself from the tradition of closed, hereditary techniques that had been passed down in his family, instead choosing to impart and disseminate his knowledge to many people. This open legacy became the driving force behind the explosive development of cloisonné during the Meiji period, leading to the emergence of numerous artisans. The sharing of techniques, unbound by specific bloodlines or power, enabled industrial-scale cloisonné production in places such as Shippomachi and the Nagoya Cloisonné Company. Kajitokichi’s actions marked a social turning point, transforming cloisonné from a secret skill into a nationally recognized craft.

With the advent of the Meiji era, cloisonné enamel began to play a significant role in the nation’s economic strategy. At that time, the value of Japanese currency was low overseas, prompting the government to actively promote the export of art and crafts, including cloisonné, in order to acquire foreign currency. Against this backdrop, the international exhibitions held around the world from the mid-19th century became an excellent stage for introducing Japanese cloisonné to the global audience.

During this period, cloisonné transformed from merely being decorative embellishments for practical items such as architectural decorations and sword fittings into pure artworks like vases and framed pictures. A clear objective guided by the government’s export strategy provided cloisonné artisans with a strong motivation to pursue the highest quality. As a result, each workshop competed in skills, leading to the emergence of exquisite techniques that are now regarded as impossible to replicate. This is a typical example of how national economic policies can inadvertently forge a cultural golden age.

In discussing the golden age of Meiji cloisonné, the presence of the two masters, Namikawa Yasuyuki and Togawa Sosuke, is indispensable. Together, they are referred to as the ‘Two Namikawas’ and gained international acclaim, each having perfected different techniques and aesthetics. The fact that Togawa’s masterpiece, ‘Cloisonné Landscape with Mount Fuji,’ was displayed as ‘painting’ in a museum at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair eloquently demonstrates that cloisonné transcended the bounds of decorative craft and was internationally recognized as a pure fine art. The existence of these two masters—Namikawa, known for wired cloisonné, and Togawa, known for unwired cloisonné—proves that Meiji cloisonné pursued and perfected two entirely different aesthetics simultaneously, characterized by intricate line work and soft artistic expression. Their mutual dedication and efforts maximized the expressive potential of cloisonné art.

Following the golden age of the Meiji era, the techniques of cloisonné rapidly diminished due to changes in social conditions. In contemporary times, the challenges faced by the entire spectrum of Japanese traditional crafts—such as a shortage of successors, a shrinking market, and difficulties in securing raw materials and tools—have also cast a shadow over the world of cloisonné. Along with changes in lifestyle, there has been a declining trend in the demand for traditional works such as large vases and framed paintings.

The reason why enamel continues to shine across eras is not solely due to its technical beauty. It is deeply intertwined with the Japanese spirit through the aesthetic consciousness of ‘harmony’ and ‘delicacy,’ embodied by the painstaking handiwork of artisans. Enamel is not merely a craft technique; it symbolizes the Japanese passion for creation, a refined aesthetic sensibility, and an indomitable spirit that continues to innovate while preserving tradition. Despite facing the challenge of a shortage of successors, contemporary artists strive to find new forms of expression, working hard to convey the brilliance of tradition into the future. Their efforts are the key to ensuring that the craft of enamel continues to shine across generations.

Inheriting and evolving Japanese traditional craftsmanship through watchmaking

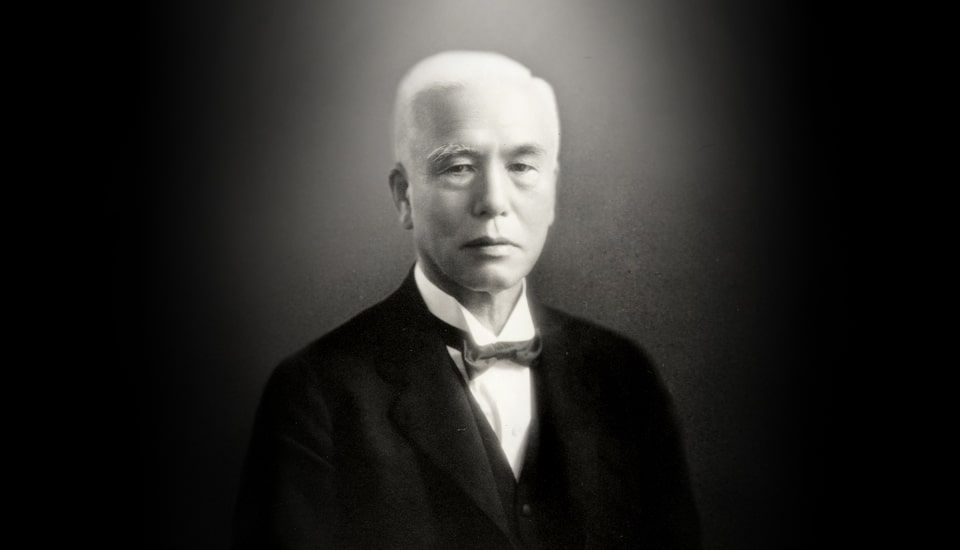

The Presage Craftsmanship Series embodies the spirit of Japanese manufacturing. This spirit is rooted in the philosophy of the founder, Kintaro Hattori, who aimed to “bring trust and inspiration to people and society.” It is refined through continuous training and a challenge to innovate. This series is not merely about ordering beautiful dials from external workshops; it is established through a positive synergy between Seiko’s designers and master artisans from various fields in Japan. Designers propose designs that inspire artisans to take on challenges, while artisans, in turn, provide fresh ideas, allowing traditional techniques to evolve in a manner suited to modern watchmaking.

This collaborative process not only produces a singular finished product but also reflects values deeply rooted in Japanese culture, which continually advances techniques passed down through generations. This signifies that Seiko positions its timepieces not merely as precision instruments, but as works of art that encompass the spirit of craftsmanship and cultural narratives. For consumers, owning a watch from this series offers a deeper experience, not only of telling time but also of embodying the rich artistic traditions of Japan and the craftsmanship that supports them.

Enamel: A warm texture and enduring beauty that does not fade

The enamel dial is highly regarded for its warm texture and the luster that does not fade over long periods. This dial is carefully crafted by artisans under the supervision of Mr. Mitsuru Yokozawa, an enamel craftsman. The process of applying glaze uniformly to the small watch dial and firing it is strongly affected by temperature and humidity, making the adjustments to the glaze components and the assessment of the finish by the artisans extremely important. This handcrafted process results in dials that possess subtle nuances, with no two being exactly alike. This slight individual variation gives each watch a unique value as a ‘one-of-a-kind’ piece, allowing consumers to experience a ‘special time’ that is uniquely theirs.

Urushi: A depth of rich and lustrous color

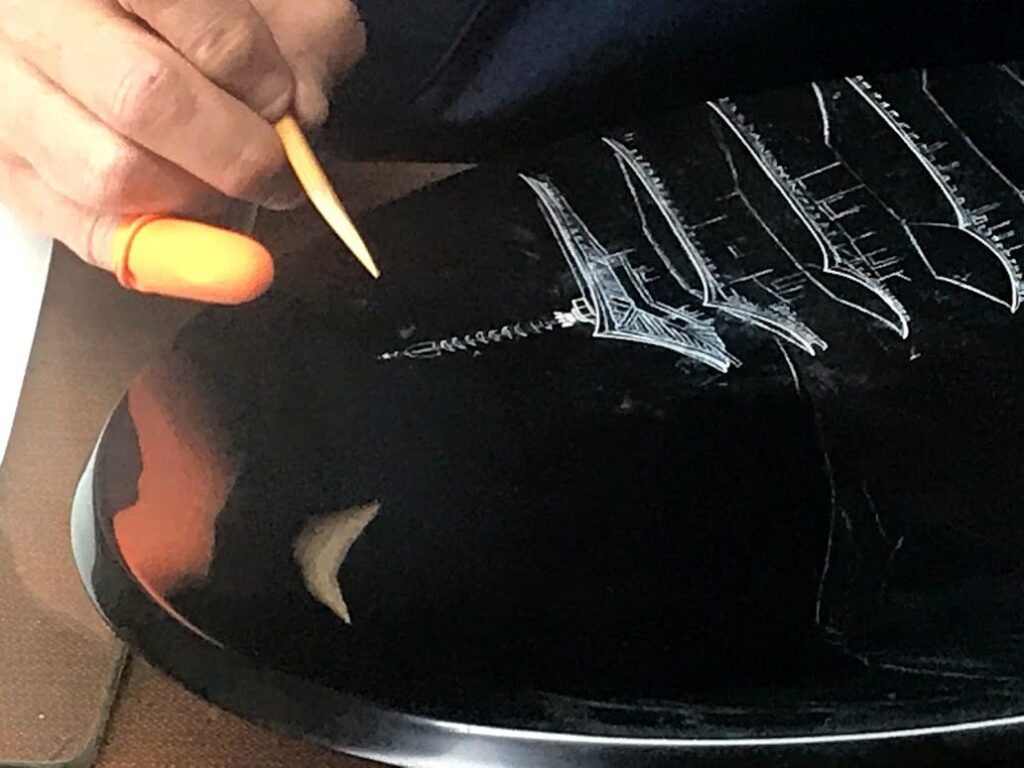

The urushi dial is known for its profound, glossy coloration unique to urushi, as well as its wet-like luster. The creation of this dial is supervised by Mr. Kazuharu Tamura, a urushi artist residing in Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture. After mastering the traditional craft of Kaga Maki-e, which is passed down in Kanazawa, Mr. Tamura developed an unparalleled intricate technique that has received international acclaim. The dial undergoes an elaborate process that involves multiple cycles of applying and polishing, requiring considerable time and effort to complete. This multilayered process generates a rich visual depth inherent to urushi and delicately alters its appearance depending on the way light hits it. Additionally, the golden seconds hand and indices add a high-contrast accent against the deep black of the urushi, further enhancing its beauty.

Arita porcelain: A fusion of delicacy and strength

The Arita porcelain dial is characterized by its pure white beauty and unique texture. This model is a creation that introduces a new challenge to the tradition of Arita porcelain, which boasts over 400 years of history, under the supervision of craftsman Hiroyuki Hashiguchi from the long-established ‘Shin-gama,’ founded 190 years ago. Achieving a porcelain that is both thin and possesses high strength, suitable for use as a watch dial, took approximately four years of research and development. Utilizing a high-strength porcelain material that is more than four times stronger than conventional types, and firing it at a high temperature of 1300°C, resulted in a dial that is hard and durable, contrary to its thin and delicate image. Notably, the three-dimensional shaping technology that expresses smooth curves and variations in height within a thickness of less than 1mm is particularly noteworthy. This delicate relief creates rounded light lines unique to ceramics depending on the angle of light, offering the owner a distinctive aesthetic experience.

Shippo Enamel: A Transparency Suggestive of the Deep Blue Sea

The Shippo Enamel dial is characterized by its sacred and beautiful colors, likened to ‘seven treasures.’ This dial is produced in collaboration with a long-established workshop of Owari cloisonné that has over 190 years of history, and it is crafted by enamel artist Wataru Toya. Cloisonné is a type of enamel decoration where glass-like glaze is applied onto a base metal and fired at high temperatures around 800°C. Since even slight variations in the composition of the glaze or the firing temperature and time can alter the hues, Mr. Toya’s highly refined skills are indispensable. The deep blue color created by this technique possesses clarity and depth, changing its appearance with the angle of light, captivating the viewer.

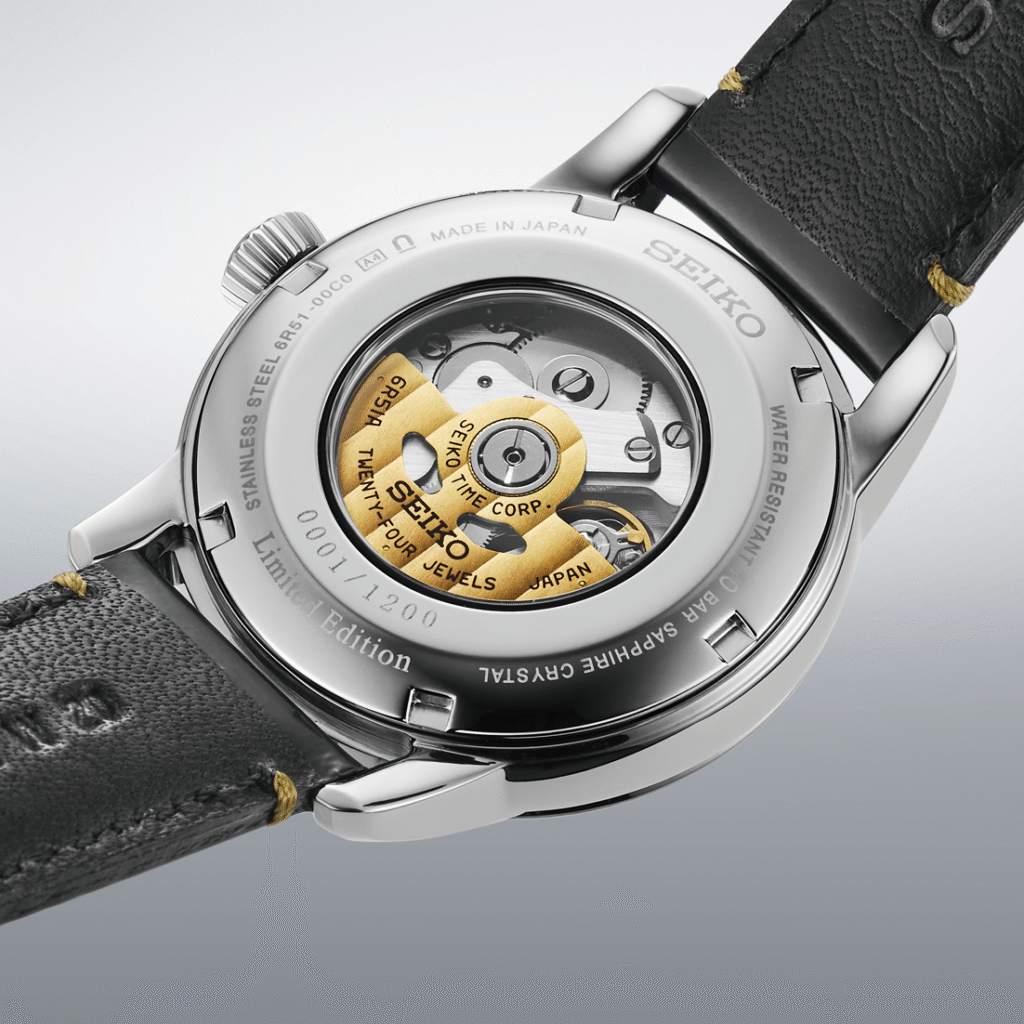

The reliable technology of Seiko

Pursuing the essential function and convenience of clocks

The Craftsmanship Series embodies the mechanical technology that Seiko has cultivated over many years beneath its beautiful exterior. At its core is a self-winding (with manual-winding) mechanism equipped with an in-house movement.

The published accuracy is often stated as “+25 seconds to -15 seconds per day” (when worn on the wrist at temperatures between 5°C and 35°C). This figure may appear modest in comparison to the strict, high-precision standard set by the Swiss Official Chronometer Testing Institute, which defines an accuracy of -4 seconds to +6 seconds. However, it possesses sufficient practicality for everyday use, and the value of the Craftsmanship Series is found not merely in its second-level precision but rather in the ingenuity that enhances its practicality.

The most notable feature is the long power reserve of approximately 72 hours (three days), which is widely adopted in recent models. This ensures that even if the watch is removed on Friday night, it will continue to operate smoothly until Monday morning without stopping. For users who own multiple watches and rotate them over the weekend, this feature brings immeasurable convenience. The elimination of the need to frequently wind the watch significantly enhances the ownership experience, making it an important aspect.

The craftsmanship that resides in the details is one of the great attractions of the Craftsmanship series. For example, the dome-shaped glass adopted in many models evokes a classical atmosphere while sometimes causing parallax due to light reflection. In this series, to resolve this visual issue, a ‘bent hand’ design has been employed, where the tips of the second hand and minute hand are slightly curved. This minimizes the distance between the hands, the dial, and the indices, thereby enhancing the ease of reading the time. This ingenuity not only improves visibility but also adds a delicate softness to the overall design of the watch, providing the owner with a sense of possessing something truly exceptional.

Furthermore, in the finishing of the case, both mirror and hairline (linear) finishes are skillfully differentiated. This allows the expression to change depending on the light, creating a texture and luxury that surpass the price range. These elements are not mere surface decorations, but rather a fusion of function and beauty aimed at enhancing the watch’s essential qualities, such as warmth of texture, durability that resists fading, and visibility. The ‘Japanese Aesthetic’ of the Craftsman Series is incorporated as an intrinsic component to enhance not only the visual beauty but also the durability and aesthetic value of the products. This philosophy of ‘Functional Beauty’ is the true strength of the brand and serves as a key factor in providing users with profound satisfaction.

The value proposition of ‘Quiet Luxury’

The Appeal of the Craftsmanship Series

The design of this series embodies the Japanese aesthetic concepts of “yukari” (subtlety) and “yo no bi” (the beauty of usefulness). In contrast to the sharp edges and robustness typically emphasized in ordinary watches, the dial of Presage is composed of soft, rounded curves that delicately change in expression depending on the light. This modest yet rich expression resonates deeply with the sensibility of the Japanese people, who have historically valued beauty in simplicity. The profound blackness of lacquer and the warm whiteness of enamel, along with the unique textures of traditional colors, create a highly compatible design that naturally blends into various everyday scenes.

For the owner, the allure of this series extends beyond mere beauty. It lies in the harmonious balance of exquisite design and high practicality. The watch achieves a comfortable wearing experience by adopting bands and bracelets that fit well on the wrist. Furthermore, it is equipped with sufficient functionality for everyday use, including dual curve sapphire glass with anti-reflective coating, high-precision calibers, and water resistance up to 10 atmospheres. These features position the watch not merely as an accessory, but as a reliable partner to accompany one for years to come.

This series encompasses essential elements that form value in Japanese culture: product quality, craftsmanship, and long-term reliability. This is not a value based merely on being a ‘status symbol’ due to a high price, but rather it is grounded in the value proposition of ‘quiet luxury’ that appreciates intrinsic beauty and the stories behind creation. Practical features such as an extended power reserve and surface treatments like Diamond Shield position the watch not just as a fashion item, but as a reliable ‘lifetime companion’ that accompanies daily life, a philosophy deeply intertwined with Japan’s ‘monozukuri’ (craftsmanship) ethos.

Moving beyond the simplistic framework of price equating to value

Traditional Japanese crafts are produced as products with extremely high added value, thanks to carefully selected natural materials, skilled techniques honed over many years of training, and the immense effort and time dedicated to their manufacture. Judging by international market standards, these should originally fall within the category of luxury products that are traded at high prices. However, many traditional crafts exhibit price competitiveness compared to similar high-end products overseas, and in some cases, they are available at surprisingly affordable prices. In this regard, watches from the Craftsmanship Series can be purchased at astonishingly low prices compared to Grand Seiko and European luxury brand watches.

At the foundation of Japanese craftsmanship lies a unique spirit known as ‘shokuninkishitsu.’ This represents a cultural value that transcends the mere act of creating products, finding worth in the pursuit of mastering one’s skills and striving for perfection. Since ancient times, Japanese monozukuri has been regarded as a noble endeavor that pours all of one’s refined sensitivity and spirit, honed through the purification of both mind and body. This spirit not only enhances the quality of products to the utmost limits but also sometimes drives creators to prioritize this commitment above economic rationality.

Japanese crafts possess a history of having emerged and developed not as lavish adornments or symbols of authority, but largely as “necessities of life” rooted in daily existence. The “folk craft philosophy” proposed by figures such as Soetsu Yanagi during the Taisho era rediscovered the “beauty of utility” inherent in “crafts that arise from the populace” and held this value in high regard. Here, the “beauty of utility” refers not merely to decorative beauty, but to the beauty of tools that reveal their true worth through use, reflecting a worldview that enriches daily life.

Such values function as cultural factors that suppress the prices of traditional crafts. Consumers tend to perceive crafts as ‘practical tools that are readily available in everyday life’ and often underestimate their value. This is because the worth of these products is based not on ‘rarity’ or ‘artistic qualities’ but rather on ‘practicality.’ In other words, the low prices of traditional crafts should not be interpreted as indicative of their intrinsic value being low; rather, they can be seen as evidence that these products are deeply rooted in domestic culture and are widely disseminated as ‘everyday tools.’ As prices are significantly influenced by the cultural context in which the products are situated, they do not necessarily align with the essential value of the products themselves.

The Value of Visiting Seiko Boutiques in Japan

The true worth of Seiko wristwatches lies in the delicate interplay of light and shadow, which cannot be fully conveyed through photographs or videos. To truly experience the value of Seiko wristwatches, it is recommended to visit a Seiko shop in Japan, particularly a Seiko boutique that offers the highest level of experience. In the Kansai region where I reside (Osaka and Kyoto), there are three Seiko boutiques located. Additionally, a new store has recently opened in Hakata, Kyushu, enhancing convenience for visitors from abroad.

Japanese Seiko boutiques are far more than mere sales points for wristwatches; they embody a unique experience that transcends functional roles. These establishments merge Seiko’s craftsmanship philosophy, cultivated over more than 140 years, with a distinctive aesthetic sensibility, offering an unparalleled space. Purchasing a luxury watch can often be a significant decision. This decision is influenced not merely by product specifications or price, but rather by a profound understanding of the story embedded in the product and the background that gives rise to it. Japanese Seiko boutiques serve as strategic points of connection that foster this deep understanding and empathy.

The existence of a Japanese original model

For overseas watch collectors, the ‘JDM (Japan Domestic Market)’ models developed for the domestic Japanese market hold a unique value due to their rarity and distinctive design. Seiko, through these JDM models, transcends ‘Made in Japan’ quality and creates a strategic rarity encapsulated in the notion of ‘Only in Japan.’ The intricate features exclusive to JDM models, such as the kanji representation on the date wheel, further accentuate their uniqueness and imbue them with irreplaceable significance as mementos of one’s journey in Japan. Thus, Japanese Seiko boutiques have established their status as ‘pilgrimage sites’ where collectors from around the world seek out special models that can never be obtained elsewhere.

The role of the boutique as a cultural hub

Visiting a Seiko boutique in Japan means not only acquiring products but also engaging with the very culture of Japanese craftsmanship. Seiko promotes the concept of ‘gracefully embodying Japanese aesthetic sensibility’ in its wristwatches, incorporating traditional cultures such as Arita pottery and plant dyeing. The boutique serves as a conduit for conveying the stories embedded in this design and the underlying Japanese aesthetics.

Additionally, the provided information includes testimonials from workshops and museums, illustrating how people feel the “importance of time” and “Japanese history” through watches. Just as artisans in the workshops constantly contemplate “how to produce 100 pieces with the same finish,” Seiko watches embody a sincere attitude of relentlessly pursuing product quality.

The boutique serves as a showcase for this craftsmanship, cultivating a deep understanding and respect for the brand among customers by visually and sensually conveying the culture behind the products. The Seiko boutique in Japan plays a global role, transcending mere product sales to act as a ‘medium that tells the culture’ where Japanese tradition and innovation coexist.

To embody a different set of values than those of European timepieces

Wearing a Japanese watch carries a deeper significance than merely checking the time or serving as an alternative to the traditional luxury timepieces of Switzerland or Germany. What these brands embody is a unique paradigm of values that sets them apart from the ‘tradition’ and ‘status as luxury items’ cultivated by Western watch culture. This paradigm is centered on meticulous technical precision, an unwavering pursuit of practicality, and a design philosophy that is deeply rooted in the aesthetics of Japanese nature.

Japanese watch manufacturers are demonstrating a strong presence in the Asian market. Seiko has launched extensive advertising campaigns in the Asia region, including Taiwan, Thailand, and Indonesia, and has introduced limited edition models for the Asia-Pacific region. By leveraging cultural and geographical affinities, they are significantly increasing brand visibility. Opening one of Asia’s largest flagship boutiques in Kyoto is part of this strategy, and it suggests an intention to convey the brand’s appeal to the entire non-Western market from the center of Japan’s traditional culture.

Furthermore, in the Middle Eastern market, Seiko is strengthening its presence. By establishing a service network in regions such as Dubai, Bahrain, and Jordan, and being frequently featured in the luxury gentlemen’s magazine ‘Esquire Middle East’, they are deliberately appealing to the local affluent class. This indicates that Japanese watches are gradually being accepted in a region that has traditionally been a stronghold of Swiss luxury timepieces.

If this article has piqued your interest in Japanese watches, I would highly recommend that you take the opportunity to experience the ‘Seiko Presage Craftsmanship Series’ at least once.

コメント